1932 The Chimneys I

What an impressive letterhead! Full of pride of ownership, the Overlack brothers present their freshly acquired factory at Aachener Straße 256 in Mönchengladbach. The chimney is smoking – an important sign of a functioning factory. And the balance sheet for 1931, which Heinrich is still working on, is also cause for celebration – despite the emergency decrees with which Chancellor Brüning governs the country and tries to restructure the German economy.

On 21 January 1932, Heinrich writes to his brother Ed, who meanwhile lives in Bad Honnef: "The balance sheet is ready in the rough; I am not working on it any further, as I want to submit it to the tax office at the latest possible date and until then there may be many postponements, but we do not know what emergency decrees Mr Brüning still has in his bosom. In any case, it is better than in 1930 and will show up to M 5000 or 6000 more profit. But I don't want to commit myself to these figures yet, since changes can still occur due to write-offs and other valuations of inventories, accounts receivable, etc. In any case, the result is most gratifying [...]."

1933 Bribe money

In March 1933, Chief Tax Secretary Hartmann of the Gladbach-Rheydt-Nord tax office examines the books of the Overlack brothers. He finds what he is looking for.

Under "Expenses", not only "Expenses for entertaining business associates" and "Hunting lease" are listed, but also "Bribes". The German term for bribe money "Schmiergeld" dates back to the days when stagecoaches were used to travel overland. There, the bribe was a fixed fee that every traveler had to pay. If the axles were not greased (in German "schmieren") regularly, the wheels would seize up and no progress could be made.

A vivid picture! The fact that one can make business friends inclined to one's business through gratuities was still taken into account in Germany as an honorable business expense until the 1995 tax year: as long as this was the case, bribes were allowed to be deducted from taxable income.

In the spring of 1933, however, Chief Tax Secretary Hartmann criticized the overly generous recognition of expenses and increased the taxable profit in 1930 and 1931 by 5,000 and 6,000 Reichsmarks respectively.

Charcoal and pencil drawing from the 1920s

© Stadtarchiv Mönchengladbach, August Stief Collection

1934 The Villa

In 1926, the textile manufacturer Walter Schubarth had the representative villa at Aachener Straße 236 built. Soon after that, his business luck must have run out, because already in 1930 the building belongs to the director Lutz Overlack. The villa is located directly next to the company premises of the "Gebrüder Overlack" and allows Lutz an extra short way to work.

"My uncle Lutz," recalls Hans Overlack (Managing Director 1963-1992) in 1998, "was first class at weathering opportunities. He was a bachelor for many years and probably still lived with his parents in Krefeld. In any case, he had no major expenses. He put his money into real estate. It is said that he lost 60 apartments during an attack on Krefeld during the Second World War. For the villa on Aachener Straße he paid only 28,000 Reichsmark* – a real bargain!"

*1 Reichsmark in 1933 equals €4.60 in 2022.

The new main warehouse of the Overlack brothers on Aachener Straße

1935 Storage facility

Around 1935, the Overlack brothers put their money where their mouth is. The existing storage and production facilities are no longer sufficient. They therefore have the main warehouse rebuilt and commission the brother of Heinrich's wife Lisbeth, Robert Gerhards, to do the job. The architect, who was born in 1898, is a senior building official in Koblenz and a planner with a great sense of space. The elongated warehouse building he designed will characterize the image of the company on Aachener Strasse until the mid-1990s. A letter from 1938 states:

"A photograph of M.-Gladbach is missing, as the factory is under complete reconstruction. We would like to point out that the main building was rebuilt a few years ago and received a special award from the city of M.-Gladbach as the most beautiful factory building after the war."

Just like Lutz Overlack's partner, Dr. Curt Stäuber, who died at an early age, Robert Gerhards also dies before his time from an undetected rupture of the appendix already in 1951.

Hunting trip: f.l. Lutz, Eduard sen., Ed and Heinrich

The photo shows Heinrich and his sons Dieter and Hans the day after a hunt. It was only during the follow-up search that they discovered the stag, which had been fatally shot the night before and had managed to escape. Now he is dead. Good hunting!

1936 Shotgun Brothers

Shotgun Brothers

The Overlack brothers share a passion – they are enthusiastic hunters. From their childhood days, their father Eduard took the three boys hunting. The photo of the joint hunting trip, as well as the hunter in the snow, probably dates from the first half of the 1930s. "Picture of Father 3 weeks ago hunting sows in the Hunsrück," Lutz comments on the portrait of the old gentleman, "the man gets younger every year."

Eduard Overlack, youngest of 13 children and thus called "et Herrjöttsche" in Rhenish by his family, dies in July 1936.

Hunter in the snow, Eduard Overlack, ca. 1933

Lisbeth and Heinrich Overlack with their children (from left) Dieter, Brigitte and Hans

1937 Late wedding

After a long bachelorhood, Lutz Overlack marries Hilde Rath in September 1937, when he is 45 years old. The wedding party celebrates in the traditional "Gesellschaft Verein" in Krefeld.

In the company "Gebr. Overlack", Lutz is the senior with a three and a half year lead over the younger Heinrich. One generation later, this will change, because Heinrich has already married in May 1921. His children Dieter, Hans and Brigitte are born in 1922, 1925 and 1928, Lutz's sons Eduard and Jürgen later, in 1938 and 1942. Heinrich appears at the wedding of his older brother with his family festively dressed up in tailcoats and medal decorations.

Lutz Overlack marries Hilde Rath

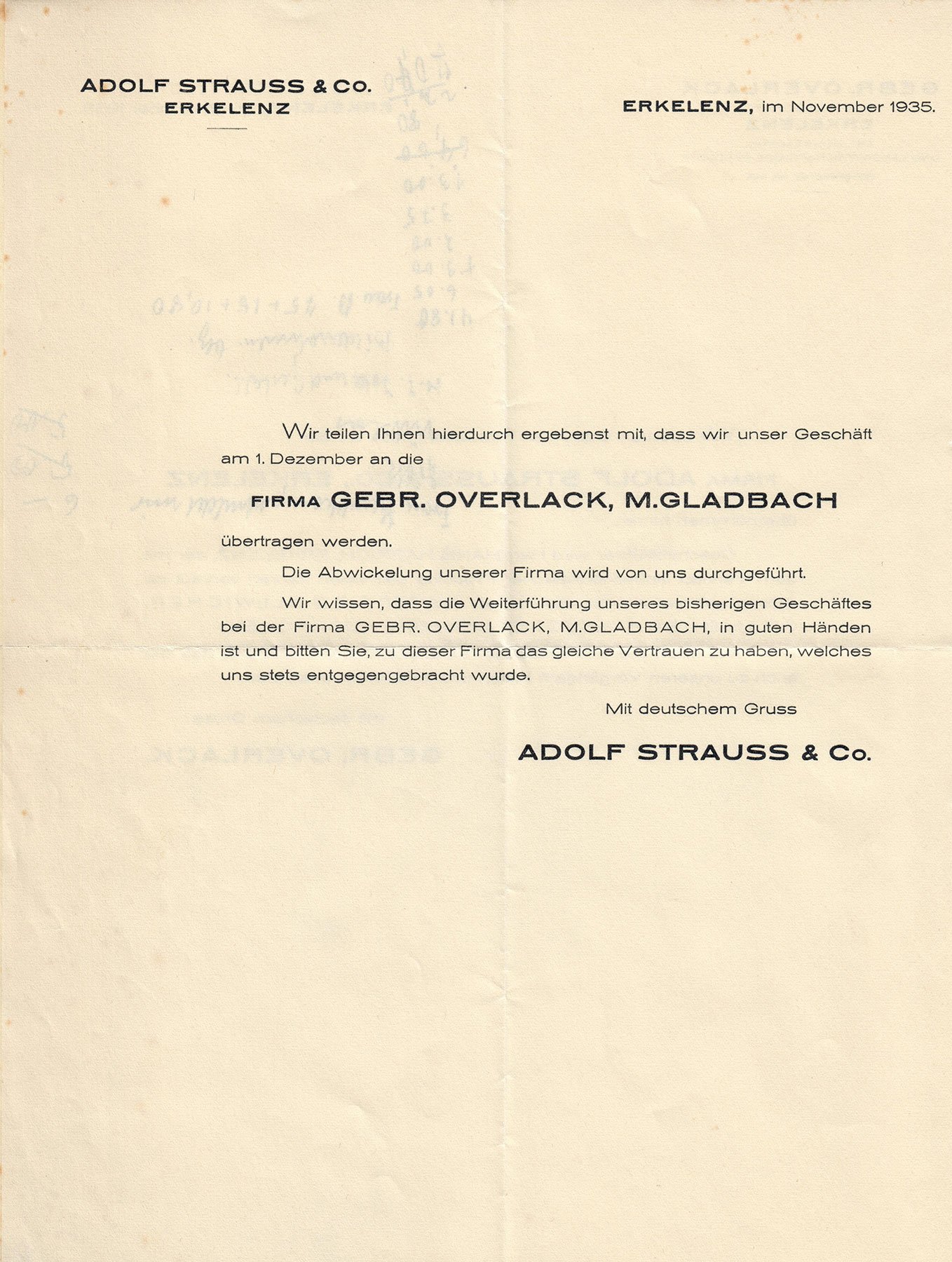

1938 Strauss & Overlack I

In 1938, the Overlack brothers apply for a trade loan of 75,000 Reichsmarks. A whole series of forms has to be filled out for this. In the detailed accompanying letter we learn more about the business of the last years:

"Our company is mainly engaged in the wholesale of heavy chemicals and all other chemical products used by the textile, leather and iron industries, and also in a small-scale manufacture of textile auxiliaries.

In December 1935, in order to extend our distribution of chemicals to agriculture, we decided to take over a Jewish fertilizer and fruit trading company in Erkelenz, which we initially leased. This company was acquired by notarial deed from the former owners, Messrs. Strauss in Erkelenz, in June 1938, after the agreement of the Aachen District President had been obtained. The purchase price was RM 22,500."

A strange paragraph, which refers in a rather vague way to a terrible phenomenon that was widespread in those years: the Aryanization of Jewish property. Heinrich Overlack takes pains to emphasize the legality of the takeover of the company; the company was initially leased in December 1935. Two and a half years later, it was acquired "by notarized purchase" and a precisely quantified purchase price was paid. Generally, these things are taken for granted – not so in the lawless 1930s, when the Germans robbed their Jewish fellow citizens not only of their entire assets, but also of all their civil rights, turning them into fair game.

As early as March 13, 1936, the Nazi newspaper “Westdeutscher Beobachter” noted the transfer of the Strauss feed and agricultural products business into "Aryan hands".

Note in the West German Observer, March 13, 1936

1939 Security in uncertain times

September 1, 1939 marks the beginning of the Second World War. The German Wehrmacht invades Poland in violation of international law and without declaring war. This is followed by a six-year inferno that plunges the continent into the deepest despair. The Germans, who cheered on the Nazis, cultivated fantasies of world conquest, were initially still revanchist and confident of victory, but later became increasingly desperate. They only found their way back into the circle of democratically governed powers thanks to the determined efforts of those they called "enemies" at the time, who were prepared to make extreme sacrifices. Almost unimaginable numbers of victims are to be mourned in almost every family of the warring nations.

In such uncertain times, people look for security in their everyday lives; this is evidenced by the "Übereignungs-Vertrag" (transfer of ownership contract) from 1939, which deals with claims of the Overlack brothers against the Wienheller company. These claims are secured by a dyeing apparatus owned by the debtors. There is no provision for a change of ownership; the pledge is simply to be treated with care and insured against fire until the goods debt is settled.

1940 Under the sign of the swastika

The letterhead dates from the time of the Third Reich, as indicated by the embossed emblem at the bottom left. Around the membership badge of the German Labor Front (DAF), the unified trade union of the Nazi state, is the wording "Gaudiplom für hervorragende Leistungen" ("Gaudiplom for outstanding performance"). Such merit badges were awarded specifically to integrate smaller businesses. The criteria on which they were based make clear the political objectives of the DAF, which was founded as the successor organization to the trade unions just a few days after they were broken up in May 1933.

With 25 million members in 1942, the German Labor Front, as a compulsory community of employees and employers, was the largest mass organization in the German Reich. The trade unions representing the interests of the employees had long since been replaced by their education in the spirit of Nazi ideology. Another instrument in this process was the performance battles in the factories, to which smaller companies in particular felt compelled to resort.

Helmut and Hannelore Strauss, about 1941 in Erkelenz, lost in Izbica/Poland

1941 Strauss family from Erkelenz –

The annihilation

80 Jewish fellow citizens lived in the city center of Erkelenz in high times. That was in 1905.

In 1941 only 17 are left. Five of them bear the name Strauss and are descendants of Salomon Strauss, who founded the first "fruit and spice store" in Erkelenz in the 1850s. At the end of the 19th century, Salomon's sons Moses and Bernhard took over the agricultural business, ran it together for a while, then separated the business and continued it in their own companies, each with their own sons, so that in the 1930s there were two agricultural businesses in Erkelenz with the name Strauss and a company headquarters in Neusser Straße: the agricultural business "S. Strauss und Söhne", which Bernhard ran with his sons Ernst and Karl, and the company "Adolf Strauss", which Moses' son Adolf ran with his brothers Fritz and Rudolf. Both companies are aryanized, with the Adolf Strauss company passing into the hands of the Overlack brothers.

What happens now to the actual, rightful owners of these two land businesses? After 1935, Adolf Strauss initially works as an employee in his former own company; when this is no longer permitted, he lives on savings, later on his wife's income.

With a lot of luck, Adolf, who married a Catholic woman and is baptized while still in Gestapo custody, survives the last years of the war in hiding in Bavaria. His three children, Erna, Grete and Kurt, who were raised Catholic, also survive the war and persecution, with Kurt "going underground" in the fighting troops. Adolf's brothers Fritz and Rudolf manage to escape to South America in time for the war; they survive in Brazil. The sisters Caroline and Erna, on the other hand, become victims of the Shoah together with their husbands.

One of the two cousins, Bernhard's younger son Karl, also manages to escape, emigrating to Colombia with his wife Gertrud and daughter Ruth in August 1938. Ernst Strauß, born in 1898, remains behind in the German Reich with his wife Thea and his children Helmut (*1931) and Hannelore (*1933). Step by step, the Nazis deprive the family of all material goods, most recently their apartment. In April 1941, Ernst, Thea, Helmut and Hannelore Strauss are assigned two rooms in the Spiesshof in Hetzerath. From here they are deported to the transit ghetto Izbica/Poland on March 22, 1942, where their traces are lost.

Description of the family fates according to Hubert Rütten, Jüdisches Leben im ehemaligen Landkreis Erkelenz, Erkelenz 2008.